Ripped From the Crypt: Vol. 2

To celebrate the Halloween season, I’m digging through the vaults and resurrecting some of my old flash fiction—stories many of you have either never read or may have long forgotten since they were first published 15 years ago.

THE HAIR

As long as Kurt Larson could remember, he had been fascinated by shaving. As a kid, he had owned one of those “My First Shaving Kits” and would lather up his face with shaving cream while his father shaved in the sink. He would mimic the man’s meticulous movements with the plastic razor, slowly and skillfully removing the cream from his own baby-smooth face. He grew increasingly excited about hitting puberty and the prospect of using a real razor to shave real hair – of having real stubble.

Since then, his voice had lowered and his body had filled out nicely. He had grown tall, and his baby fat had been replaced with toned muscle. Now, at 16, he was shaving weekly and had the beginnings of a nice beard – when he decided to skip a shaving session, that is. Kurt was quite pleased with his looks, with the exception of several black hairs growing between his eyebrows. Thick, coarse, and altogether unsightly, these wiry strands created a confluence of eyebrows otherwise known as the dreaded “unibrow.”

Kurt was extremely insecure about his unibrow. He hated it, but at the same time, he didn’t think shaving the hair between his eyebrows would be a good idea. A razor lacked the precision and maneuverability needed to contain the unsightly patch properly. This was a problem. He decided that he would tweeze the hairs; that way he could shape his eyebrows and hide any evidence of his unattractive brow-bridge. This would be the beginning of a rigorous grooming routine that Kurt kept secret.

Kurt shuddered to think what people might say if they found out that he, an athletic, straight high school boy, was plucking his eyebrows every week. He made the JV basketball team that year and had become quite popular with the girls at Haddonwood High. He had sprouted to a healthy 6’2” and was one of those handsome All-American athletes who end up on the covers of magazines and the fronts of cereal boxes.

‘You never see a unibrow on a Wheaties box or the front page of the sports section,’ Kurt thought. Amidst basketball practice, dances, parties, and all the extra-curricular activities that comprise teenage life, Kurt kept up his secret routine of tweezing between his eyes every week. He noticed the hair grew back faster and darker, a realization that mildly aggravated and altogether terrified him at the same time.

There was one hair in particular that Kurt had grown fond of plucking. He found himself looking forward to gripping the coarse black strand and slowly pulling it from his skin, revealing the entire length of the hair, along with the root. He was intrigued by how long the actual hair was under the surface. He had come to enjoy plucking his eyebrows. The sting, the slight twinge of pain he felt when he yanked out a hair, had become a pleasurable sensation.

Kurt would never acknowledge his “manscaping” habit. It was more than a habit – it was an addiction. He would idly rub a finger between his eyebrows, and if he felt any indication that a new hair had sprouted, he would go to the bathroom between classes, step into a stall, pull out his tweezers and the small pocket mirror he now kept in his book bag, and pluck the hair rapaciously.

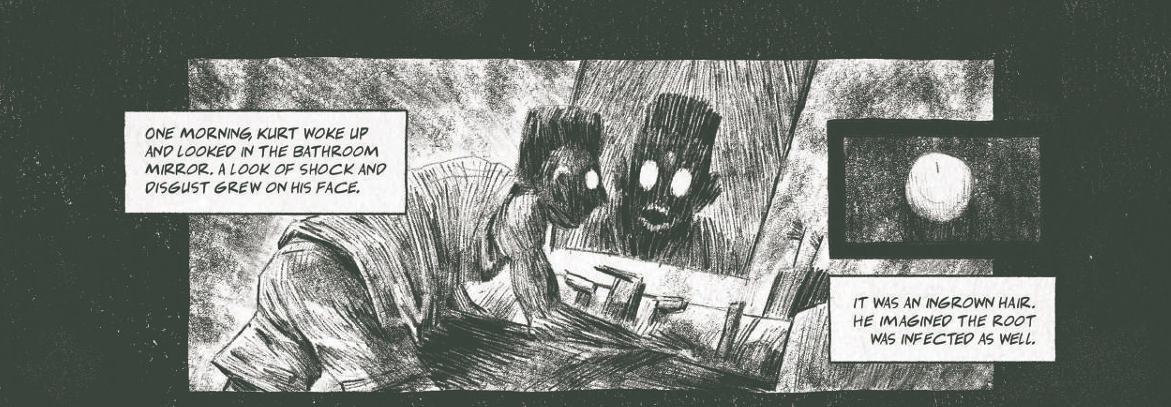

One morning, Kurt woke up and looked in the bathroom mirror. A look of shock and disgust grew on his face. A red sore had formed over the spot where his favorite hair grew. It was tender to the touch and Kurt thought he felt something inside it, probably pus. It was an ingrown hair. He imagined the follicle was infected as well.

A blemish was of great concern to Kurt, who took pride in his immaculate complexion. He was worried that if someone were to study the blemish closely, someone like Sandy Jensen, his date for the prom, they could discern that the blemish was an ingrown hair. This would lead to all kinds of questions – questions Kurt would have to dodge or flat-out deny. He couldn’t imagine the emasculation in having his prom date ask, “Do you pluck your eyebrows, Kurt?”

This was an emergency, so Kurt reached for his shaving kit to retrieve his trusty tweezers, as well as some rubbing alcohol and peroxide. Under the bright fluorescent lights, he leaned over the sink and examined the sore. Using his left hand, he pushed together the skin around the blemish. With his right hand, he carefully punctured the sore with the tip of the tweezers. At first, there was blood, then a clear liquid oozed out, followed by a disgustingly foreign, milky substance.

He squeezed out all of the pus and other secretions, then cleaned the wound with peroxide. Once the gash was thoroughly sanitized, Kurt took the tweezers and searched for the hair itself – it was his favorite, after all. After some prodding, he found it, curled up in the wound like one of those facehuggers from Alien, coiled up in its egg, waiting to spring forth.

Kurt carefully pinched the bristly hair with the tweezers and pulled slowly. At once he felt that familiar twinge of pain, the tingle of pleasure dancing along his nerve endings. He continued pulling the hair and was rather pleased at how strong the strand was – almost like a guitar string. The hair must have been an inch long.

The sight was grotesque – a red, bleeding wound right between his eyes, a long, coarse hair pulled slowly – and the boy was both delighted and disgusted by the sickening sensation tickling the back of his brain. And so Kurt continued pulling, the hair growing thicker and darker with each tug of the tweezers. The hair was easily eight inches or more now, dangling between the boy’s eyes as he continued grabbing the base and pulling outward. Sweating, tears collecting in the corners of his eyes, Kurt thought the hair must have been close to a foot long when he felt some resistance from within the wound. He had been plucking for nearly 20 minutes, and his arm and hand muscles were strained from the continuous gripping and pulling.

He decided he had been gentle enough. He yanked hard and felt a tug under his skin. The hair hadn’t broken off, however. Instead, it hung between his eyes as he examined the sore in the mirror. Beneath the blood and torn skin, Kurt saw what looked like a small black scab, no bigger than the head of a pin. He picked up his tweezers for the last time and focused on the base of this scab, where the hair went into it. He assumed this must be the infected follicle, and though he was in pain, he was rather excited to pull it out completely. Kurt yanked at the base of the hair, and the black thing burst out, a geyser of blood, pus, and plasma erupting from the wound once more, oozing down the bridge of his nose. He set the tweezers and the hair aside and went back to cleaning the wound.

Peroxide, then rubbing alcohol – he loved the way it burned and set his head on fire. He took a cotton swab and pressed it firmly against the wound until the bleeding stopped. He looked down at the hair, wondering how long it was – close to 20 inches or so? For the first time, the star athlete set eyes on the black scab at the end. It reminded him of a plug or a stopper you might use for the sink. Upon careful examination, Kurt noticed that the scab was shiny. He held it up to his eyes under the bathroom lights and realized that it was not a scab – it wasn’t even organic. It was, in fact, a microchip. An integrated circuit, like something from a motherboard, smaller than the head of a pin, thinner than a fingernail.

The revelation was petrifying. Kurt didn’t know what was more alarming – the fact that this thing had been inside him or that he had ripped it out. There was a solder joint connecting the hair to the base of the chip. In his hands, the hair felt more like a wire, or possibly an antenna. He thought about bugs, those little feelers on their heads tingling with sensitivity and excitement.

Kurt suddenly felt sick to his stomach. His vision was blurry, and a strange metallic taste was on his tongue. His chest convulsed and his heart beat violently. His muscles burned deep, his eyelids twitched uncontrollably. All at once, he slumped over and slapped hard against the linoleum, his head crashing against the porcelain toilet on the way down. A considerable chunk of flesh and hair above his right ear had been peeled back in the fall. Blood leaked out onto the cold linoleum floor.

Several hours later, Kurt’s father found him lying unconscious. He held his son in his arms, examining the deep gash above the boy’s ear. He lifted the flap of skin and pinned it back, revealing a small panel filled with buttons and tiny switches. Quietly and casually, Kurt’s father pressed a few buttons and flicked the switches in a numerical sequence. He folded the skin back over and held it in place for several seconds, just long enough for the skin to join itself back together – no stitches, no scar, not even a scab.

Kurt’s eyes flickered. His father helped him up and walked him to the bed. Kurt lay there, his arms and legs moving in abnormal patterns – a motor reflex test. While his son rebooted, Kurt’s father went back to the bathroom and cleaned up. He knew the system startup would take precisely 10 minutes, which was more than enough time to clean up the blood and put everything back in order.

Kurt wouldn’t remember the hair or the scab-chip. His father retrieved the tweezers and closed the bedroom door behind him. Sure, Kurt would have questions, but they could be easily answered. Maybe he had hit his head against the hardwood floor during practice, receiving a mild concussion. In any case, whatever lie his dad created would be easier to stomach than the truth: Kurt wasn’t a regular boy – he wasn’t even human.

There would come a time when Kurt and his father would have “the talk,” but it wouldn’t be today, and his father was thankful for that little bit of comfort. It was one thing to explain puberty – the birds and the bees – but something else entirely to explain the complexities of organic engineering, of synthetic tissue, and the nature of disguising a machine as a man.

Later, Kurt woke up and stumbled to the bathroom. After washing his face with soap and water, he leaned over the sink to examine the space between his eyebrows in the mirror. He ran his finger over a small black hair growing just above the surface of the skin.

Artist Miquel Muerto illustrated THE HAIR for STRANGE KIDS CLUB MAGAZINE VOL. 7, which you can view here.

A WELL-PLACED GRAVE

There are a lot of misconceptions about my line of work. I’m a gravedigger, plain and simple — I ain’t no caretaker or mortician or some son of a bitch who sells you the burial plot. I’m the swingin’ dick that’s putting you down, tucking you in for the long sleep.

I was, anyway. There ain’t much use for old boys like me anymore — not with Caterpillar excavators and backhoes. I ain’t never been much for technology. A flashlight’s good, a cigarette lighter’s better — that’s about all I need. I’m a shovel-and-pickaxe man, yessir, I am.

First thing you do is measure — length, width, and depth of the casket. Then you examine the ground. Avoid hard clay if you can, but don’t go digging in soft either. Once you’ve got all that figured out, you’re ready to dig.

Most people’ll tell you your standard grave is six feet deep. They’re wrong. That’s a major misconception about my line of work right there. The modern grave’s only four feet deep. Why? Well, caskets used to be made of wood. The wood would rot along with the corpse, collapse under the weight of the dirt.

Burying it six feet down — beneath the sod, where the grassroots are — kept that collapse from making a sinkhole. Believe me, the last thing you want is a cemetery full of damn sink spots. Get a heavy rain and every last one of those graves will wash out.

Now the modern casket, that’s a different story. These days, the body’s laid to rest in a fancy box made of wood and steel, polished up real nice. You can buy the bare minimum for eight hundred bucks, but the nicer ones’ll run you four grand easy.

Then it all goes into a concrete box with a flat lid — like an Egyptian sarcophagus — a vault to keep the elements off that expensive casket. Some companies line the lid with the same kind of tar they use to install car windshields. That shit’s sticky as hell, and it never dries. Seals the concrete tight. Keeps it from breaking or sinking, which is why you don’t have to bury it as deep.

A typical grave’s four feet deep, eight feet long, three feet wide. After measuring, the first thing you do is remove the sod. Sod’s tough and holds together, so you’ve got to peel it back first. I like to think of it like cutting brownies out of a pan.

You start with a flat-bladed shovel, cut the sod outlining the grave — straight down the middle too — then cut across every eleven inches or so. You’ll have sixteen pieces of turf, which is a hell of a lot more manageable than one big slab.

Pry up the sod, shave off a little on the bottom to make it flat, then set it aside. Now you can start digging. And this here’s important: you’ve got to remember you’re putting something back in the ground, so you’ve got to compensate for the displacement.

You can usually dispose of the top two feet of dirt, then shovel the rest into a pile for filling later. Keep at least a wheelbarrow’s worth from the top layer — you’ll need it. Always have extra dirt on hand. Words to live by.

Anyway, that’s the start. If I open a grave a day before the funeral, I throw a couple sheets of plywood over the hole so some damn idiot doesn’t fall in. Good idea to tarp both the hole and the dirt to keep folks from nosing around.

The mortuary here uses artificial grass rugs to cover the dirt — keeps it tidy for the service. After the funeral, after the goodbyes, that’s when I get my check. Then I start filling the grave.

Filling it in’s straightforward. You stand in the grave, on top of the concrete box, and use a square-nosed shovel to pull dirt toward you. I usually bring a cooler, have a few cold ones, smoke a few cigarettes. Ain’t nothing finer, I’m telling you.

You want the dirt about three or four inches from the top. Compact it with your boots. Then lay the sod back down — make sure it sticks up a couple inches — and lay a sheet or two of plywood on top. I drive over it a couple times with my truck to press it flat.

When done right, the grave should look even. The grass’ll be matted from the plywood, so I use a leaf blower to fluff it up, blow off the extra dirt. Then I take a little time to arrange the flowers folks left behind. And that’s it. Job done.

Machinery makes things too impersonal these days. I take pride in the fact that I’ve buried thousands of people — people whose names I can’t seem to shake. People who were loved. Still loved. Missed by those they left behind.

I don’t know how many more graves I’ve got left in me or how many paychecks I’ll collect, but I do know this:

I won’t be buried here.

I won’t be put down by no son of a bitch in an excavator.

I’m getting cremated. No fancy coffin, no concrete vault. Just a cardboard box from the crematorium — maybe a coffee can.

By Ewell "Dummy" Johnson

THE WASP QUEEN

Lime green paint slowly drips

Down the wall behind

A woman's face, so white

And pallid, like vampire flesh.

A wasp crawls over her teeth

And tastes the sweetness

Of her tongue.